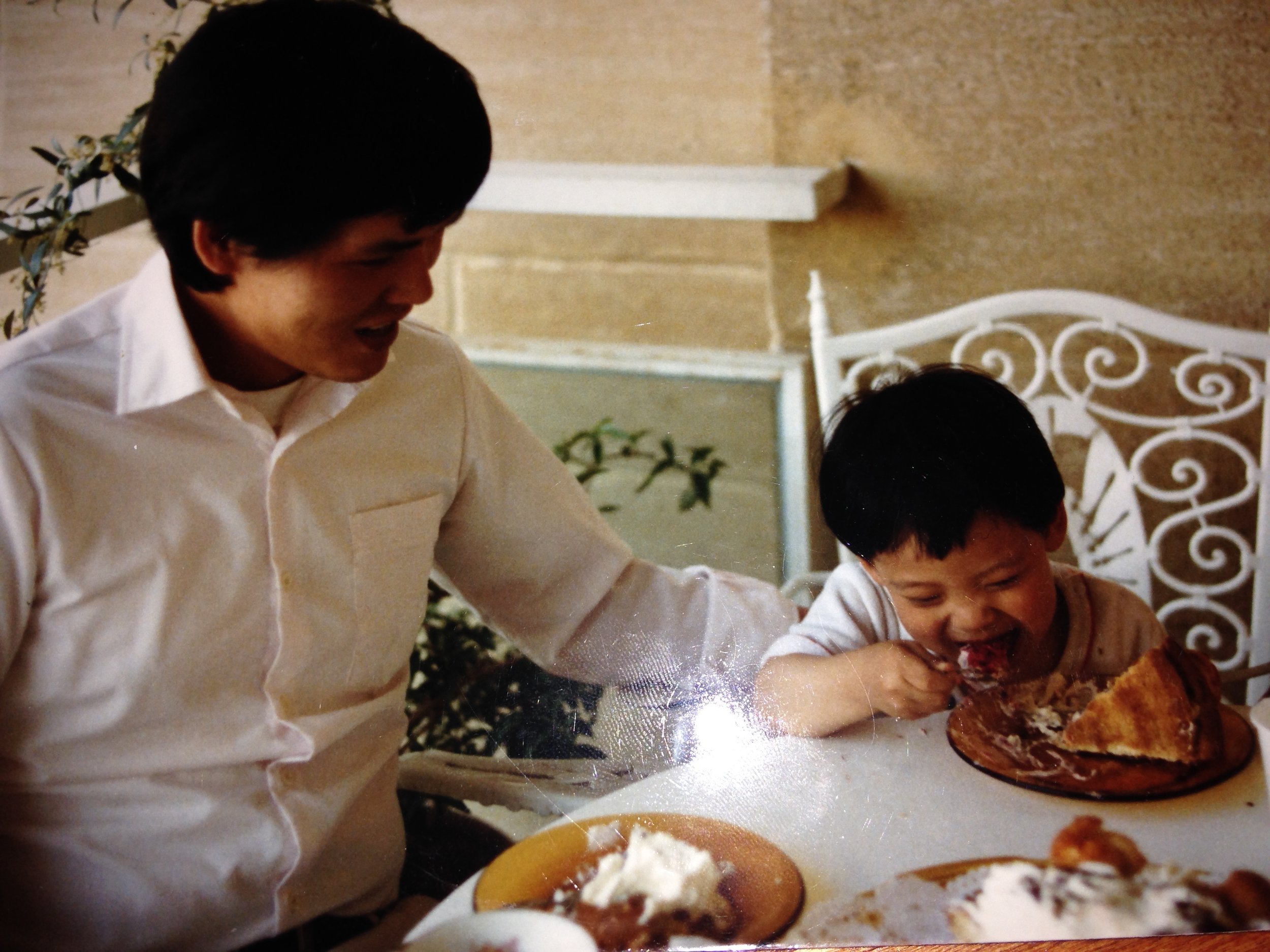

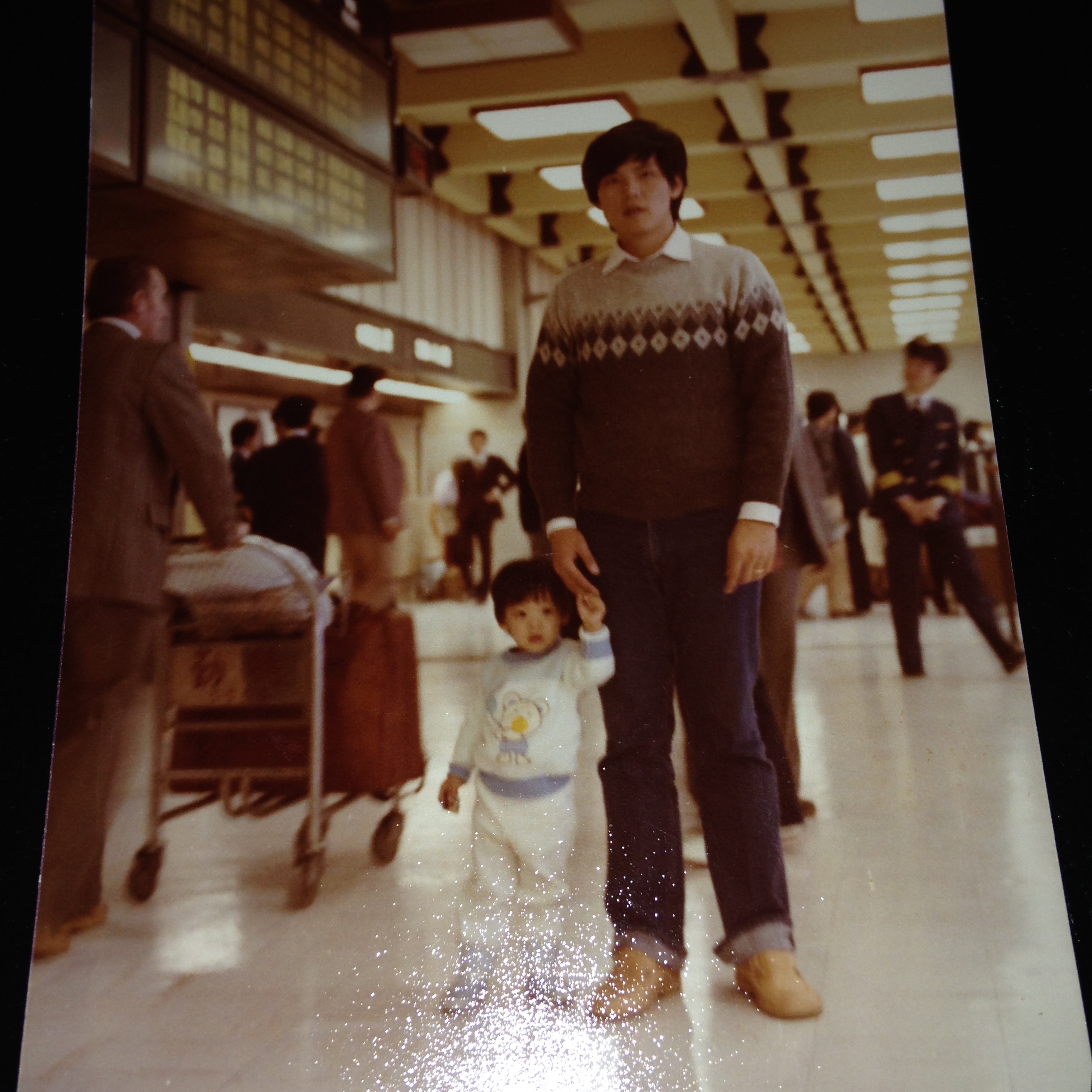

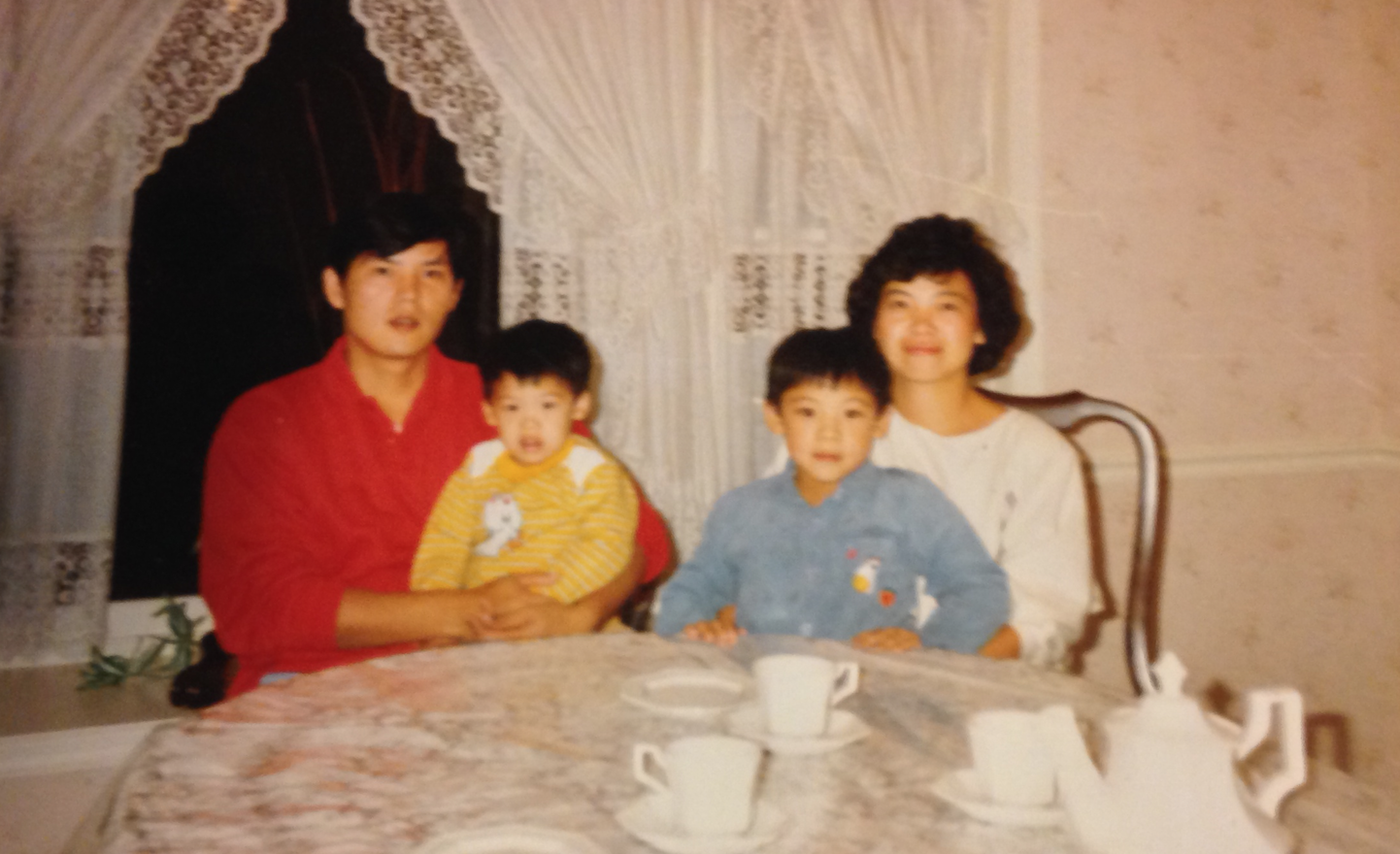

I grew up watching the effects of myotonic dystrophy (dystrophia myotonica, DM) take its toll on my father – first, his hands would not open properly when he used tools like a hammer. Later, it was muscle weakness that led to constant tripping and falling, once causing him to tumble down a flight of stairs. He had a cardiac arrhythmia, sometimes causing his heart to beat as slow as 25 beats per minute at night – only recently was he fitted for an implantable cardioverter-defibrillator to ensure a normal heartbeat. I hated watching different symptoms appear over time, but there wasn’t anything he could do – there were (and still are) no approved treatments for DM. Although I’m sure he was frustrated with losing various functions over time, he never made it obvious to my family – he seemed to accept that his health would deteriorate bit by bit each day.

As a teenager, I was very frustrated and confused – why my family? But I also had no choice but to accept the situation. We didn’t know anyone else with DM and knew almost nothing about the disease. We were also in a constant state of denial – we never truly faced the possibility that my brother and I had a 50% chance of inheriting DM. I studied biology in college, thinking that I would go to medical school and later help heal the sick. I thought, “maybe I can help people with diseases for which we do have treatments” – but I wasn’t completely convinced. After I graduated, I joined a research lab at Harvard Medical School, where I studied biomechanical forces in the cardiovascular system. There, I met graduate students who were passionate about science and its capacity to impact the world – they were doing work to understand the cause of disease at a basic level, so that treatments could be developed. After learning about my family, they encouraged me to study DM and obtain formal training as a scientist. A year later, I entered the Harvard-MIT Division of Health Sciences and Technology, where I sought out co-mentors, David Housman and Chris Burge, who would help me gain the interdisciplinary skills necessary to embark on my professional and personal journey to make an impact on DM research.

I could go on with this story, but I have told this story many times in the past. The first time was about 5 years ago, in front of several hundred people, gathered together for the 8th International Myotonic Dystrophy Conference in Clearwater, Florida. Back then, I was still a graduate student at MIT, and I held a singular goal of doing the science necessary to get us closer to a cure. The path forward seemed clear – publish high impact publications describing my scientific work, get an academic job leading a lab, and keep moving forward at 110% speed (“Wang-speed”, according to my colleagues). But 5 years have passed, and interestingly, while I am now indeed in Florida, I am in a new place, mentally and figuratively. I am writing a new story – but this time, the story is more complicated – and it includes many new characters.

The “old” story I told myself was that we would all work together to “cure a disease”. I knew that many moving parts would be involved in reaching this goal, but it wasn’t until recently that I had a fuller appreciation of all of these parts. I was likely naïve about how winding and tortuous the journey ahead would be – and in another 5 years, I will probably look back at today and pass a similar judgment. But what this means is that I am continuing to learn and grow, and that I am not blind to the challenges that lie ahead. I acknowledge that many pieces must fit together so that we can reach our destination. I'm writing a "new" story day by day - and below I describe 5 broad areas/themes that are playing important roles in this new story:

Training and educating a team of researchers

Gaining financial and institutional support so we can do research

Recruiting expertise that isn’t currently available in the DM field

Learning from and sharing our findings in the broader scientific community

Building connections with other people going through similar struggles

1. Training and educating a team of researchers

I’ve now been at the Center for Neurogenetics at the University of Florida for about a year and a half. It has been wonderful to have my lab next to the labs of Andy Berglund, Maury Swanson, and Laura Ranum – we are all focused on studying diseases such as DM, and we all have expertise that is complementary to one another. This means that we each have unique lab equipment and techniques, and different ways of approaching similar problems, leading to unexpected ideas and collaborative efforts. We have the opportunity to work together in ways that most academic scientists never get to experience throughout their entire careers. But one challenge that must be surmounted in order to reach the true potential of this collaborative model is that we must find efficient ways to train and educate not only individuals in our own labs, but ways to share expertise across labs.

As a new assistant professor, I have been learning how to better lead and teach (not something you learn in graduate school), as well as finding ways to facilitate dialogue across multiple labs. One program that we successfully implemented using funding from Promise to Kate was a summer computational biology internship program for undergraduates, where each of our 4 labs supervised 2 undergraduates. Students worked closely with full time lab personnel and presented their work at the end of the summer. The hope is that these students will continue working with CNG labs on DM-related topics throughout their entire college career.

CNG Undergraduate Scholars and Mentors: First row (L-R): John Leatherman, Zacharias Anastasiadis, Andrea Murciano, Daniela Valero, Lainey Williams, John Cleary (PhD,) Jana Jenquin (BSc), Quinn Silverglate. Back Row (L-R) Faaiq Aslam, James Thomas (BSc), Melissa Hale (MSc)

2. Gaining financial and institutional support so we can do research

As the leader of an academic laboratory, I am responsible for obtaining funding to pay for salaries of lab members, as well as lab reagents. The University of Florida provides space and infrastructure to perform research, as well as a “start-up” package that provides funding to jump-start the lab and generate preliminary data that can be used to obtain new funding. The National Institutes of Health is typically the largest source of funding for academic labs, but we also collaborate with drug companies, who sometimes provide funding as part of the collaboration, and we also rely on funding from private sources, such as donations from PTK. The NIH application process for grant funding can be grueling and challenging – your application is typically reviewed by 3 other scientists, and discussed in a panel. Only a small fraction of grants are funded, and that fraction varies depending on the specific NIH institute that administers the funding, as well as overall funding rates to NIH as determined by the government. Grants focused on DM are often administered by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) or National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases (NIAMS); funding rates for a 5-year grant from NINDS and NIAMS in 2015 were 19% and 16%, respectively.

Together with colleagues at UF and other institutions, I have been applying for numerous NIH as well as private foundation grants. There are negatives and positives associated with grant writing. It does take a lot of time and can prevent one from “doing science” in the lab. On the other hand, it has required me to think very clearly about the proposed science and get it down on paper; often, I come up with new ideas while I am writing a grant because I am forced to explain the work and organize it in a manner clear enough for others to understand.

Private funding such as that from PTK is absolutely critical for us to move as rapidly as possible in the lab. To be competitive for NIH funding, we always need to generate preliminary data to demonstrate the feasibility of the work we are proposing. By having access to additional, non-NIH funds, we have the resources to generate preliminary data, keep our science going prior to receiving NIH funding, and in the end, leverage the private funding as “seed” money to win larger NIH grants that sustain our research.

3. Recruiting expertise that isn’t currently available in the DM field

In conversations with many other scientists and the general public, it is clear that DM is still viewed as primarily a muscle disease. This is untrue, and in some individuals, the most important symptoms are caused by defects in the central nervous system. DM is also a brain disease. This means that in order to address the needs of DM patients and to identify treatments, we need the expertise of neuroscientists familiar with how the brain works, how to measure brain function, and how to develop therapies that can cross the blood-brain barrier. One of the motivations to better understand brain defects in DM, especially symptoms of profound sleep/fatigue, is Ona McConnell, one of my lab members who was diagnosed with DM1 in college. One of the most challenging symptoms for Ona is feeling exhausted almost all the time, and this has motivated us to begin projects specifically to study regulation of sleep in DM model organisms, such as flies and mice.

I am also really excited to have started a new collaboration with Gary Bassell, neuroscientist and Chair of Cell Biology at Emory University – we are working together to understand CNS defects in DM. Gary has extensive experience in the Fragile X and Spinal Muscular Atrophy fields, and is applying his neuroscience expertise to DM. Gary in turn has recruited a cadre of additional neuroscientists at Emory to also work on DM, including Han Phan (pediatric neurologist who runs an MDA clinic), Zhexing Wen (Dept. of Cell Biology), Peter Wenner (Dept. of Physiology), and David Rye (Dept. of Neurology).

I personally do not have the neuroscience expertise that Gary does, and I would say that the entire DM field is lacking in robust neuroscience expertise. It would take my lab many years to gain that expertise, and that time investment would detract from the other work we are currently undertaking. The lesson is that when you really need a hammer for the job, you can improvise and use your shoe – but if you’ve got a lot of nails to deal with, going out and getting a hammer is well worth it. There are still lots of additional “nails” to deal with in DM and we need to continue bringing in specialized expertise where needed (another understudied area in DM is the gastrointestinal tract).

4. Learning from and sharing our findings in the broader scientific community

Lance's first poster as a graduate student.

Lance Denes, a graduate student in my lab, and Belinda Pinto, a postdoc in my lab, recently traveled with me to San Diego for a conference focused on RNA-protein interactions in the brain. This was a 2-day symposium (~300 attendees) just before the larger Society for Neuroscience (SFN) conference, which attracts ~30,000 individuals each year. There were talks and posters featuring research on ALS, autism, Fragile X, SMA, and DM (including a talk I gave, and posters by Lance and Belinda). Following this first 2-day meeting, Gary and I also organized a mini-symposium as part of the SFN conference, where we invited 6 guest speakers to discuss the role of RNA localization and translation in genetic disease. In my talk for the mini-symposium, I highlighted CNS features of DM, and described some preliminary data from our collaboration with Gary's lab. It is always interesting to attend meetings focused on multiple neurological diseases, because we are able to learn how the basic building blocks of cells interact to function in normal and disease contexts; many of the same players pop up in multiple diseases, and important insights are made by acknowledging these commonalities.

The final talk of the 2-day RNA-protein meeting was given by Frank Bennett of Ionis Pharmaceuticals, and was especially memorable because it described recent data from clinical trials for SMA (spinal muscular atrophy) using a new drug (nusinersen), conducted in partnership between Ionis and Biogen Idec. In contrast to typical Type 1 SMA in which infants die within a few years of birth, infants receiving this drug improved in motor function milestones. What was most notable for me wasn’t necessarily the talk itself, but the questions and comments from attendees following the talk. The amazement and excitement in the room was palpable, as many scientists and clinicians knew that these results represented a turning point in our ability to treat genetic neurological disease. One individual became emotional as he described how, in the past, he saw and [unsuccessfully] treated kids with SMA – but the future would never be the same. Another individual characterized the trial results as a testament to the important basic science work performed by numerous labs leading up to this point, which allowed the community to understand the genetic defect at a molecular level, develop methods to correct that defect, and bring them full circle into patients to improve their quality of life.

Ionis and Biogen have recently conducted a Phase I/IIa trial for DM, which addresses peripheral (muscle) symptoms of DM (UF is a trial site). We are all eagerly awaiting results of this trial to know whether the drug is safe, and whether it has a positive impact on disease symptoms. It will also be very exciting to work toward developing a similar approach that can be taken to address the CNS symptoms of DM.

5. Building connections with other people going through similar struggles

Eric Hutchinson in Orlando - final week of his Anyone Who Knows Me tour.

A few months ago, I saw a Facebook post about Eric Hutchinson, who is a singer/songwriter who wrote about his own decision to get tested for DM1. As I read his story, I noticed interesting parallels – we are about the same age, lived in Boston, and have DM1-affected fathers who enjoy woodworking and playing guitar. I reached out to Eric and was able to meet him in Orlando on the last week of his tour. It was great to connect and talk about issues that rarely get discussed in everyday conversation – once we sat down to drinks, there was an immediate sense of an unspoken shared experience. Eric is eager to get more involved in the DM community, and I look forward to seeing how his talents and connections can help our community in yet to be discovered ways.

There are so many people out there that are affected by DM (at least 1:8000, and more, if you count family members). But like Eric H., I didn’t know any of them in high school – I think most DM families start out feeling alone and isolated. I have now met many people through attending Myotonic Dystrophy Foundation meetings, starting support groups in Pennsylvania and Massachusetts, and through the Promise to Kate foundation. By meeting all of these individuals, I have felt less alone, and my efforts have evolved into a group effort. I know that we can accomplish much more by working together, with all of our talents, resources, and connections. For me, the Promise to Kate community plays a unique and important role in organizing this group effort. Meeting David, Elizabeth, Charlie, and Kate Conte played an important role in my decision to move to UF. I knew that they were invested in the same issues that I was, and that we would be able to work together towards a shared vision. I have known Kate for about 2 years now, and it has been amazing to watch her grow and learn. I don’t want to let her down, and want to keep our research moving as quickly as possible. I know that the PTK community holds the same goals, and look forward to keeping my “Promise to Kate” as best as I can.

More than science

We as scientists need to do a better job of connecting with non-scientists, and explaining how our work affects everyone. The 5 broad areas mentioned above are just some that I’ve been thinking about lately, but there are also others that just won’t fit into this blog post. I hope it gives you some insight into what we are doing in the lab and how it fits together with the efforts of PTK.

In the end – while good science is what will enable us as a community to treat DM – it isn’t just about the science. It’s about connecting with other people who share similar goals and aspirations, and finding ways to work together in order to reach them. In the beginning, DM Research Chose me – but today, because of all the amazing people who were also “chosen by DM”, who are sharing this journey together with me – I choose DM research. Working together, we will have the strength and motivation to never give up – and the talent, infrastructure and resources needed to tackle DM.